What is Your Ad’s Takeaway?

Posted: 11/12/2017

Advertisers are edging away from brash sales patter. Today even the pushiest sponsors might redden to recall the time when the basketball player Shaquille O’Neal, on signing for a reported $121mm, complained: “I am tired of hearing about money, money, money, money, money. I just want to play the game, drink Pepsi, wear Reebok”.

Today it’s more de rigueur to make ‘emotionally engaging’ ads. Yet many ads still carry an information payload, even if this is less often about which celebrities endorse the product and more often about its benefits, pricing and so forth. But it’s still important to ask how this payload, and the effectiveness of the resultant takeaway, should be measured.

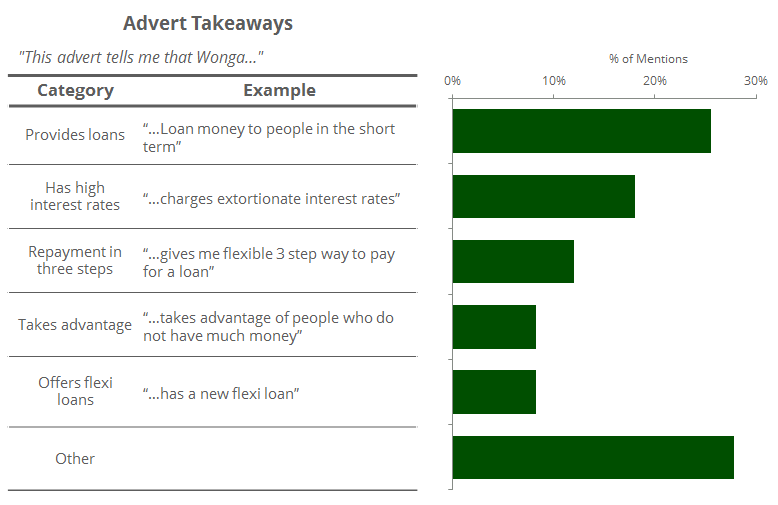

A spontaneous takeaway question can capture the different message impacts and their relative frequencies. The figure shows an example of this for Wonga. Even the relatively clear message of their advert generates a wide range of takeaways – from the literal, about providing loans and repayment in three steps – to the thoughtful, about taking advantage of people and high interest rates. These latter examples, in particular, highlight how an ad’s takeaway can be a complex cocktail of content and existing beliefs. By measuring spontaneous takeaway, you can test both these intended and unintended consequences and thereby adjust the messaging to improve impact.

The advert can also be examined from an ‘information theory’ perspective by evaluating the advert’s information gain and evidential strength (analogous to Kullback Leibler distance and conditional probability, respectively). Information gain is gauged by how much people’s beliefs could be changed by an advert’s content. For example, the Wonga advert contains more information if only 10%, rather than 90%, of people already know about flexi loans. In other words, is the payload news? Meanwhile, evidential strength determines whether the ad actually does change beliefs. This can be undermined in two ways. First, the content might be unclear or confusing. Second, when combined with existing beliefs, the claims may not be credible.

Taken together, being informative, offering clarity and having credibility are the three key attributes needed for an advert to carry an effective payload. Combined with spontaneous takeaway, this can be used to ensure that an advert both delivers a message, if that’s the aim, and that this message lands correctly, thereby avoiding the conclusion: ‘They cynically paid this basketball player an outrageous sum of money to feign how much he likes our product and then added that to what they charge me . . . grrrrr’.