Chances Are: Lying on your CV

Posted: 04/06/2019

“Only about 5% of job applicants have lied on their CVs, mostly by inflating their qualifications”

We recently overhauled our interview process, which caused some internal debate about whether we should cross-check candidates’ CVs more methodically. We were concerned that a significant proportion of resumes are embellished to some degree. But we needed more information. For example, were our concerns justified, where do people tend to exaggerate, and so forth? This note highlights the main findings of our subsequent research.

Our first insight is that people generally agreed with our intuition on prevalence. Overall 53% of respondents think people are fabricating their CVs, suggesting it is routine practice. Interestingly, we don’t see any significant demographic signature for those predicting higher or lower prevalence, though presumably some underlying personality trait for scepticism is driving the results across the population.

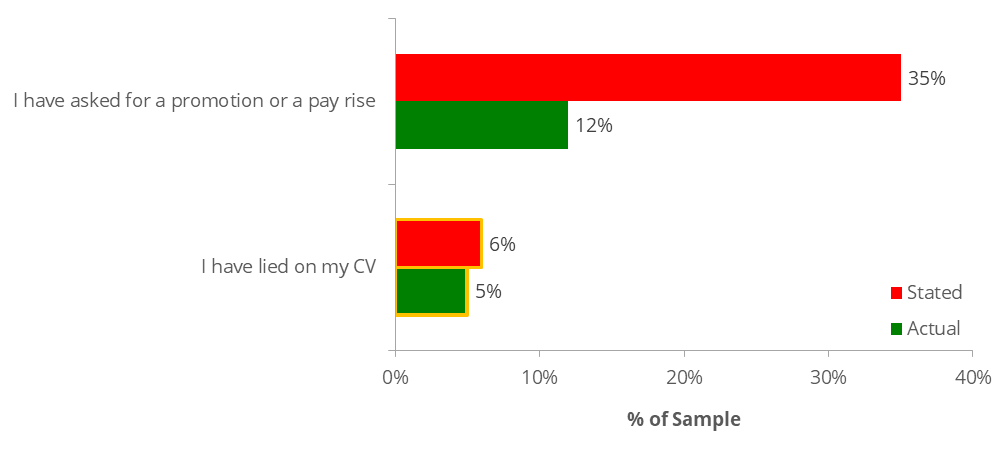

But is lying on your CV really as commonplace as we all think? Given that deceit is a social taboo we employed the Unmatched Count Technique, a method for anonymising responses so as to measure the true underlying rate, to gauge the actual prevalence (see here for details). It turns out that the workforce isn’t nearly as dishonest as we think. We estimate that only 5% of the population have actually lied on their CVs.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that so few people have padded out their CV given the seriousness of the consequences. Providing false information in a job application is fraud and can result in legal action, cost you your job and damage your reputation. As an extreme example, a cleaning lady in Greece was recently handed a 10 year prison sentence for claiming that she spent an extra year at elementary school.

Our third finding is that the people who lie on their CVs aren’t ashamed to admit to it. When we asked people directly the prevalence rate was 6%, very close to the true underlying rate. So not only are most people making honest job applications but, amusingly, even those that aren’t are honest about their dishonesty. This contrasts with other job-related topics, such as asking for a pay rise, where people actively lie about having done so (see above graphic).

Finally, we found that most of the cheaters were, like the Greek cleaner, overstating their education. Given it’s relatively easy to obtain that kind of external verification as part of reference collection, that would seem like the place to focus. In the end, only 1 in 20 candidates are likely to have embellished their application, so any checking process needs to be proportionate. But incorporating such cross-checks certainly seems justified based on our evidence.