Chances are: Job Move

Posted: 12/11/2019

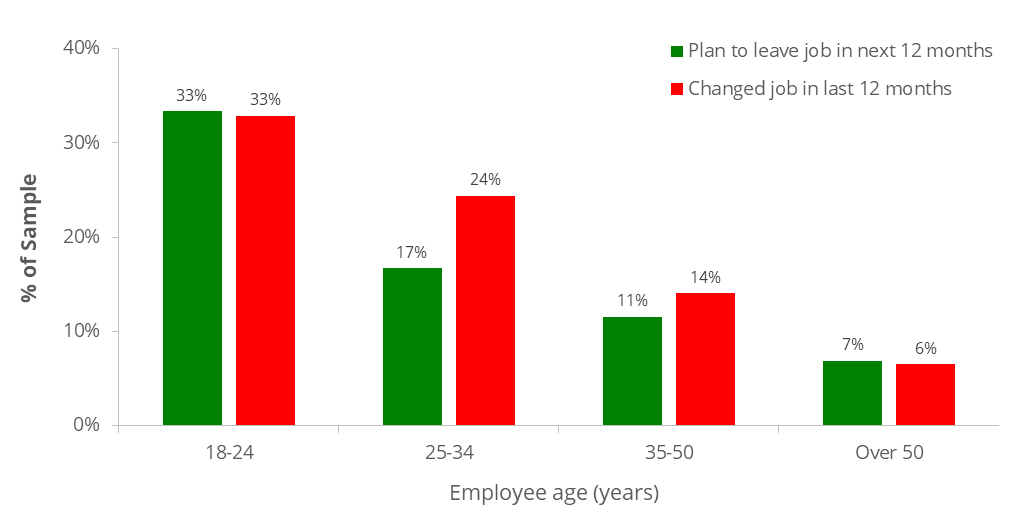

“Under 25’s are five times more likely to change jobs than over 50’s”

People don’t like change. In fact they actively avoid it. In behavioural science there is a name for this tendency – the status quo bias. It is the reason we repeatedly choose the same well-known brand or stick with the default option despite the available alternatives. We wanted to explore what role this cognitive inertia played in the likelihood to change jobs. We were also interested to find out if there’s any truth behind the belief that millennials’ are more frequent job-hoppers.

Accordingly, we asked a nationally representative sample about their intentions to leave their current job in the next 12 months and found 15% planned to do so. Then, to test forecasting accuracy, we found a similar proportion (16%) have actually changed job in the past year. So people are accurately and reliably predicting job changes overall, rather than mis-estimating the future and, by extension, exhibiting some form of bias.

Interestingly, the only significant predictor of both intending to move and actually moving jobs was indeed age, with factors such as gender, income and living in London irrelevant. Millennials are far more likely to jump ship than boomers. Ok Boomer, so the data is suggestive. However it doesn’t directly address the question of how much job hopping older generations did when they were younger. And perhaps it’s no surprise that younger workers tend flit between jobs when they can expect to receive an 8-10% pay rise in return.

Meanwhile, whilst the relationship between planned and actual behaviour is self-consistent overall, it does diverge for midway age groups. Specifically 25-34 years employees are churning jobs much more than they anticipate. So they are exhibiting a status quo bias which fails to anticipate job changes that are then materialising, such as redundancy, head-hunting, and so on.

The ability to forecast staff turnover has important implications for employers. For example they need to anticipate recruiting requirements. But more importantly, they can also intervene to stop the best staff leaving, head off the damaging effects of higher staff turnover caused by leadership or morale problems, and so forth. Our research demonstrates how actual employee churn can be both forecasted by employees but also their employers.