Context is King: How Seemingly Irrelevant Details Influence our Decisions

Posted: 09/04/2021

Behavioural science shows us that seemingly irrelevant task features dramatically influence consumer behaviour. As such, any research undertaken outside of the relevant context, like Qual, Quant and Conjoint, is distorted and potentially misleading. But there is a solution.

The idea that people know what they want is as ubiquitous as it is beguiling. Who would willingly believe that their behaviour is decided on a whim? Yet the evidence emphatically demonstrates how people’s preferences, beliefs and actions are hopelessly malleable and, as a result, incoherent. In this article we detail one such finding, consider its implications and discuss some solutions.

A wealth of behavioural science has shown that seemingly irrelevant contextual details influence our decisions in a myriad of unnoticed ways. People can be nudged by changing the default options, re-framing decisions and increasing task complexity. In short, context is king. Or, to borrow from Peter Drucker, context eats preference for breakfast.

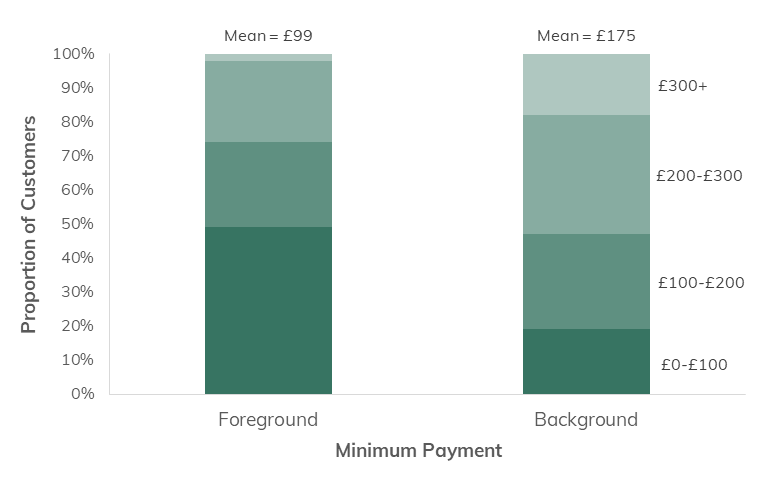

Figure 1: The Malleability of Credit Card Payments1

The chart shows a good example of these findings. People are given a credit card statement where the minimum payment is either harder or easier to find. Foregrounding that small number compared to the outstanding balance re-frames the payment choice. In this context, people make smaller payments. Conversely, when the minimum payment is recessed, their payments are 70% higher.

These types of findings are good news if you work in sales or marketing. They mean that in principle you can persuade anyone to do anything. All you need is to be armed with the right insights and then re-design the customer’s choice environment accordingly. Just as Bill Murray wins Andie MacDowell’s heart in Groundhog Day, given enough attempts, it is indeed possible to sell sand to the Saudis.

But the findings are more problematic if you are designing new products, pricing your services or trying to do pretty much anything else. Unless your research faithfully recreates the buyer’s decision context, it will inevitably fail to accurately forecast their behaviours. This means traditional methods like Qual, Quant, and Conjoint are all heavily distorted and thereby fatally flawed.

What’s the solution? A/B testing circumvents the problem because the context is real. But A/B testing has its own limitations. For example, you can only test what a firm is able, or willing, to put into market. Hence, the approach we’ve adopted in the past is to use an A/B test method, but within in a replica of the real-world decision environment using paid participants.

This is the best of both worlds. You get the rigour of a randomised controlled trial. Malleable participant behaviour is fomented under the same conditions as the real-world. You can evaluate all kinds of crazy ideas that the Exco would never let you A/B test – excepting, of course, that with enough time and patience, you can persuade anyone to do anything.

1. Stewart, N. (2009). The cost of anchoring on credit card minimum payments. Psychological Science, 20(1), 39-41.